Going global to keep it local

October 26, 2018

As a college student, Tyler Burns, teacher of Global Politics and Environmental Systems and Societies for the Upper School for Girls, became intrigued with the issue of food access and its effect on the environment. “I came away with this pretty passionate view that if we could localize the food systems and provide access to clean, healthy food for everyone, a lot of the issues in the world would be reduced,” he said.

While this idea seems naive to Burns now, he said he still believes that food availability is “a baseline issue that needs to be solved before many others.” His passion for broadening access to food and localizing food sources took him to a two acre farm in Johannesburg, South Africa, in order to learn about permaculture. Permaculture is a combination of the words permanent and agriculture (see sidebar to learn more). “We could conceive of permaculture as an alternative route for development, or at least to tackle some issues in development in Africa,” he said.

Forty years before Burns’s time on the farm, his teacher in Johannesburg helped design one of the earliest permaculture farms. Burns and his teacher educated people living in dense urban developments on how to maximize their space by growing food on small plots of land and up the sides of their house.

Burns was beckoned back to the United States by his brothers’ weddings, after which he presented at the Washington State Permaculture Convergence. After Burns’s presentation, a woman asked if he wanted to manage her 10 acre homestead on Camano island, and Burns accepted. The owners had horses and cows, but according Burns, “It was mostly old orchard and cut grass, but they wanted to take the next step and plant more trees and design a food forest (an idea in permaculture). We hosted educational events, we did farmers markets, we had our own farmstand, our nursery had 5,000 plants that were all edible or useful in some way, and we had a food forest in the three acres that weren’t pasture. They now own a bakery in Mount Vernon called Shambala bakery where they use produce from the farm.”

As Burns puts it, “The business model wasn’t there, but we had an amazing time.” After leaving the farm, Burns and his partner backpacked around South America. They periodically worked on organic farms to supplement their travels, through the organization World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF). WWOOF connects volunteers and organic farms around the world, according to their mission statement, “linking volunteers with organic farmers and growers to promote cultural and educational experiences based on trust and non-monetary exchange, thereby helping to build a sustainable, global community.” People like Burns work at these organic farms in exchange for food and a place to stay.

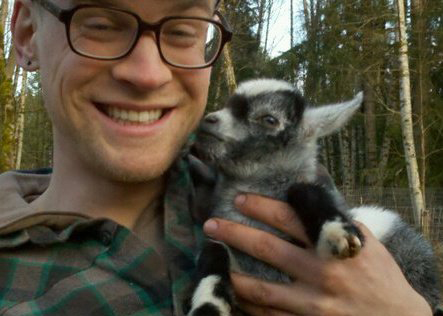

Burns then went to Hawai’i through WWOOF and worked at a botanical garden for a year with tropical plants from all over the world. He then took care of a permaculture farm down the street from the botanical garden, while its owners were on an extended vacation on the East Coast of the United States. Burns said that this garden “had every fruit tree you could imagine; papayas, all the different kinds of bananas, plantains, and an ice cream bean tree; citrus and guava and sweet potato fields as far as the eye could see, and chickens. What they really needed help with were goats.”

Despite Burns and his partner not having any previous experience with goats, they took care of them for many months. “We made cheese, sold it in town, ate a lot of cheese and drank a lot of milk,” he said. We consumed a gallon a day, at least, of product.”

After about three years in Hawai’i, Burns and his partner came back to the mainland and worked odd jobs before Burns became a teacher in the Tacoma public school system. While Burns is no longer working in agriculture, he hopes to share his extensive knowledge on the subject, especially permaculture, with the wider community.

Burns said that he believes the best way to achieve food sustainably is to eat self-grown food. Community Service Agriculture (CSA) baskets are a way to source one’s produce locally and support farms in the area. According to Burns, “Customers buy shares in the beginning of the season for a few hundred dollars, and they’re guaranteed a box of produce a week.” Burns took his Environmental Systems and Societies class to Wild Hare Organic Farm on River Road, in Tacoma, where people, such as USG History teacher Jeff Freshwater, pick up their produce through the CSA program.

According to Burns, CSA baskets are beneficial to farmers because they incur most of their expenses at the beginning of the growing season, before they have crops to sell. CSA members pay for their baskets up front, which helps offset the costs.

Burns believes, however, that the most beneficial choice a consumer can make is to eat less meat. “A large portion of our arable land is used to grow grains and soybeans for cattle, whereas that energy, all that land, could be used to grow food for our consumption, and it would provide us with many more calories because calories are lost once they’re consumed by the next trophic level,” he said. Additionally, cows produce waste that contains nutrients that can pollute waterways and that releases methane, which is more potent than carbon dioxide in terms of its ability to trap heat in our atmosphere and contribute to the greenhouse effect. The hooves of cattle compacts the soil, which destroys its ecosystem.