Colombia Insight: Q & A with Sandra Bush

photo courtesy of Americas Society/Council of the Americas

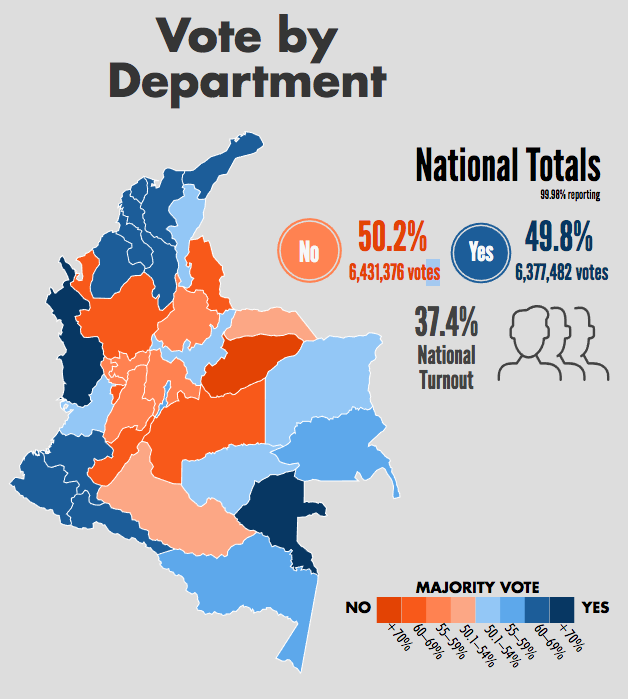

This map shows the breakdown of the Colombia vote for peace accords, which lost very narrowly.

October 13, 2016

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Spanish: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia), also known as FARC, started as a guerrilla movement in 1964 and has led an armed conflict since its inception. Throughout FARC’s violent history, the group is estimated to be responsible for over 12% of all civilian killings in Colombia. FARC was involved with the war on drugs in Colombia, using the drug trade and kidnapping to finance their movement.

After 52 years of conflict, a ceasefire accord was signed on June 25, 2016, but the accords required a referendum before being put into place. On October 2, the Colombian people voted “No” to the peace accords that would have ended their half a century long conflict with FARC. The vote lost 50.2% to 49.8%.

Annie Wright’s own Sandra Forero Bush, the Upper School Girls’ Business & Entrepreneurship director, has been personally affected by the Colombian Civil War. Ms. Bush, who was born and grew up until the age of 12 in Colombia and is a dual Colombian-U.S. citizen, has family and friends who still live there. She shared her thoughts and perspective on the violence and the peace accord vote.

Inkwell: Colombia has been in civil war with guerrilla rebel groups for 52 years. How has this conflict affected you personally?

SFB: I am thankful that my experiences are mostly peripheral (by this I mean I was not directly affected in the way so many have been, losing loved ones or being personally hurt) though they certainly have had an impact on the way I understand the world. You have to also know that the guerrilla conflict has been deeply intertwined with the drug war, so sometimes it was hard to differentiate. I have specific moments that definitely stick out in my head: growing up, we had a time when the names of the school buses were painted over to avoid “standing out” when potential for kidnapping was high. I had several classmates who had to leave the country due to death threats. I’ve had relatives and friends caught in roadside “checks” by guerrillas which ranged from basic money/jewelry threats to, in one case, a shooting after they attempted to drive through the block. (She was ok, though she had a long hospital stay…. I have since lost touch with her…). Probably most significant, when I was there in ’92-’93, we had bombs going off in Bogota. One went off about four blocks away from where I was, and in a spot where I’d been about 45 minutes earlier. That probably hit closest to home. It also makes you realize how random these things are and how important it is to go about life with no fear.

Inkwell: The Colombian people just voted “No” to the peace accords proposed by the Colombian government that would end the civil war. Why do you think the people in Colombia don’t want these accords put into place?

SFB: It is a very polarizing decision, and sadly it is a country that, due to its long history with this, is apparently more apathetic than anyone realized. Only 38% of the population voted – that’s an insanely low turnout for something so historic and critical. Out of the 13 million or so votes, the “no”s won by about 55,000 votes – that is an incredibly tight result. So yes, there are some people who don’t want the accord in place, but it’s important to recognize that almost as many WANTED it.

As to why those that voted no did so, my main sense is that there is a desire for “justice” that was not met. They want to make sure that the leaders of the guerrillas are sent to jail – that they pay for their crimes. And it makes sense! However, there are those that would argue that letting a dozen or so “heads” reintegrate without paying for these crimes is a small price to pay to be able to help the millions of victims of the war, and the thousands of kids who are recruited into the guerrilla yearly. It is about creating a better more peaceful future, and sometimes you have to swallow bitter pills in the process.

In addition to this sense of justice, there were some additional social and political issues that became intertwined with the yes and no vote (pro current president vs. pro ex-president/opposition leader, and pro social progress vs. pro family values). These also drove some of the turnout for the no vote, and it is leaving a very bitter taste in people’s mouths.

Inkwell: You have family living in Colombia. How do they feel about the vote?

SFB: It’s pretty split. Most of my family voted Yes. A few were pretty vocal in their belief for No. Those that voted no feel like they’ve been vindicated and are happy with the result. Those that voted yes are mostly pretty depressed about the low voter turnout, outcome and the impact on those poorer and more impacted communities. The despair on the Yes side is very tangible. There is a real sense that an amazing opportunity has been lost and that we are headed to much darker times again. For a country very weary of war, the hope of peace was incredible. I guess, like many in my family and friend circle, I have a hard time understanding how people could not reach for that possibility. There is fear about where this leads us and whether anything can be salvaged at this point – or whether we will be back at war come 10/31 (when the ceasefire technically ends).

Inkwell: Voters have stated they voted “No” because they felt voting yes was letting the rebels get away with murder. Do you agree with their sentiment?

SFB: I understand it, but, as I said above, I think you have to look at it from a holistic, generational perspective. It’s less about those few people and more about how do we reintegrate the thousands of folks who have felt like they had no option.

There has been some talk that IF the leaders of the FARC go to jail, so too should many politicians who have enabled the FARC and the paramilitaries that rose up to battle the FARC some years ago…If some pay, all should pay, goes the sentiment.

Inkwell: Out of your family who live in Colombia, how many of them have been affected by the civil war’s violence?

SFB: It has been indirect – or, at worst, “nearby.” Some family have homes/farms out in the countryside that they have been unable to visit at times in the past years because of fears for safety. I do have friends who were much more personally affected – who had family members kidnapped or assassinated. It’s hard to find anyone who hasn’t had some impact, really. My family is lucky to not have been directly affected. How travel happens within the country (road travel vs. air travel) has also changed (for the better) in recent years. Where one could never drive from Bogota to Medellin, for instance, some years ago for fear of roadblocks and violence, the roads have been mostly secured, which allows for people to get to know the country better. However, the more rural the areas, the less this is the case.

Inkwell: How do you feel about the fact the majority of those who voted “No” are statistically the least affected by the violence, whereas those who voted “Yes” to the peace accords have been affected the most by the civil war?

SFB: The map clearly shows this to be a trend. I think there were many who got that and also voted yes – people who understand and work with civil society who were hoping to see a change. People who were hopeful for peace for them and their children. Many of my friends and family who haven’t been directly affected voted yes for this reason. BUT, yes, the trend definitely shows that those most directly impacted wanted peace. They are sick and tired, so it’s not really a surprise. One of the “memes” that came out of this whole thing was the idea that those whose kids would go to war (as soldiers or as recruited FARC) voted yes, those whose kids are safe at home/in school voted no. I think that’s telling.

Despite the “no” vote, the Nobel Committee awarded the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos on October 7 for “his resolute efforts to bring the country’s more than 50-year-long civil war to an end, a war that has cost the lives of at least 220 000 Colombians and displaced close to six million people.” The committee went on to say “The award should also be seen as a tribute to the Colombian people who, despite great hardships and abuses, have not given up hope of a just peace, and to all the parties who have contributed to the peace process. This tribute is paid, not least, to the representatives of the countless victims of the civil war.”