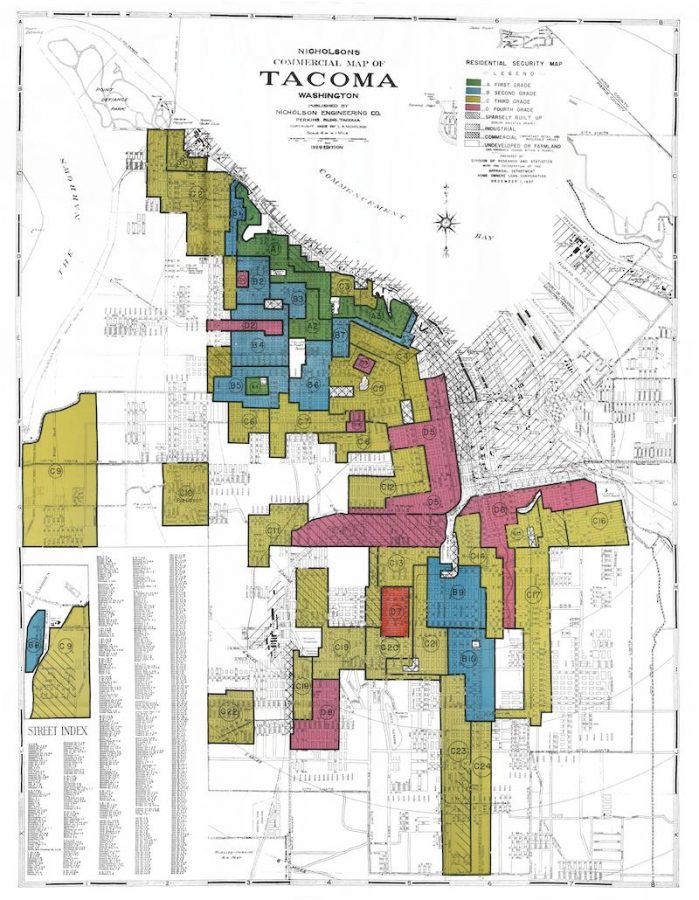

1937 map of redlined Tacoma from the Mapping Inequality online archive. Following the New Deal, banks created these maps of cities to outline the risk involved in providing loans to each neighborhood. This was explicitly determined by the racial demographic of those living there. Neighborhoods with high amounts of people of color were labeled with red for high risk. This meant that those living there could not access loans to purchase their homes or businesses. Hilltop has historically been one of those neighborhoods.

Turning Gentrification into Centrification: a Vision for the Future of Hilltop

May 1, 2021

The Hilltop neighborhood in Tacoma, Washington began experiencing the full effects of gentrification in the 2000s, resulting in the continued displacement of local residents and businesses.

According to Roberta Schur, the community development manager in the real estate department at the Tacoma Housing Authority (THA), an organization working to provide affordable housing in Tacoma, there were multiple forces behind this gentrification. Mainly, “People were getting priced out of Seattle, so they started moving to South King County. As prices continued to escalate throughout the county, they then got pushed down into Pierce County,” she said. Since Hilltop was an affordable neighborhood, many of the people from Seattle who migrated to Tacoma chose to move there. The increase in higher income families from Seattle then raised the neighborhood’s median income and consequently the price of housing.

Gentrification occurred as a result of the Tacoma Link Light Rail as well. “As soon as it was announced that the light rail was going to go through the Hilltop, speculation started to happen. People started selling and buying property up thinking they were going to be able to make a lot of money off of it,” Schur said. This led to increased attention from private investors, who purchased properties in Hilltop. Instead of developing these properties immediately, many of these investors decided to wait until the light rail is finished so they can maximize their profits.

Given Hilltop’s history as a primarily Black community, local residents and businesses have been particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of gentrification. “Because of redlining and other institutionalized racism, a lot of BIPOC [black, indigenous and people of color] people have not been able to purchase their homes or hold onto that generational wealth that a lot of other families can,” Schur said. Since many residents and businesses have been denied the opportunity to own their space, as rent prices rise, they have no choice but to pay more or be priced out.

However, there is still hope that longtime Hilltop residents and businesses will be able to preserve their community. According to Brendan Nelson, the President of The Hilltop Action Coalition, a grassroots organization that advocates to improve the quality of life for Hilltop residents, “We know that gentrification is here, and we know that there’s nothing we can do about that, but what we can change is the displacement.”

For development to occur in a way that benefits the current community instead of harming or displacing it, development must focus on centrification instead of gentrification. “When we think about centrification, we’re really thinking about: how are people that are currently in the community being a part of this [development] and not being displaced,” Nelson said.

An example of centrification in action is the Tacoma Housing Authority’s (THA) development project in Hilltop. THA is currently working on developing four parcels of land in Hilltop and plans to create buildings in these parcels that will provide residential spaces for affordable housing and commercial spaces for use by local businesses.

To include residents in this process, and ensure that the project amplifies the community voice instead of stifling or changing it, THA facilitated multiple community engagement programs to hear from the Hilltop community before they began the actual development of these properties. These programs involved long term outreach with Hilltop residents and businesses in order to hear their concerns about and hopes for the development project.

In the latest community engagement program, THA collaborated with Mithun, a Seattle based design firm, and Fab-5, a Tacoma based arts organization, to put together the 2019 #DesignTheHill Community Development Plan. This involved the several month long facilitation of multiple design and planning workshops, where organizations and residents in the community came together to help plan what THA’s development will look like. Schur said that a major goal in putting together these groups was learning, “How do we teach a community to design itself and how do we design these buildings in a way that really captures the history and the culture of the Hilltop and speaks to peoples’ dreams for the future.”

Throughout these processes, THA focused on ensuring that everyone in the community had a voice. “We didn’t want to run a community engagement process, your typical thing, where you get about 20 people in a room, the same squeaky wheels that always complain about everything and perhaps didn’t have long term ties to the Hilltop. So the outreach was really intentional to make sure that we reached out to African American folks and people who had long ties to the Hilltop,” Schur said.

By getting the community to participate in development planning, THA was able to incorporate the needs of residents throughout the project’s design. For instance, Schur said, “One of the things we learned is that people don’t like walking down M.L.K. [Jr. Way] because it’s noisy and dirty, and so people would actually prefer walking down the alleys if they were a safe place to be,” and as a result, “One of our initiatives is to do alley activation in the Hilltop so that they become fun inviting places to be.”

In terms of who will benefit from the affordable housing THA is building, during the community engagement process, THA received feedback that, “This needs to be affordable to people who live here today and it needs to include those people that got displaced from Hilltop,” Schur said. While THA normally allocates housing to people based on a preexisting waitlist, the organization decided to change the lease-up process to accommodate this need.

In addition to planning development around the needs of long-time residents, an important aspect of achieving centrification is empowering and preserving the small, often BIPOC owned, businesses that have historically called Hilltop home. This doesn’t mean that buildings containing businesses cannot be redeveloped. Instead, developers should work with small business owners to support them through the transition and ensure that they can afford to keep their space when development is over.

In THA’s development project, one of the parcels is home to two historic Hilltop businesses: Mr. Mac Ltd., a men’s clothing store, and Terry’s Barbershop. Throughout the process, according to Alyssa Torrez, a program specialist for the real estate department at THA, “We [THA] are working with them to give them a temporary relocation, and then once the construction is done, they’ll come back into that space.”

When filling the commercial space in each parcel, Torrez said that THA is additionally, “working with smaller businesses that are black owned or BIPOC owned to bring them into the community,” in order to, “add to the culture and the feel of the community and also give opportunities to people that haven’t had them before.”

While it is important to provide Hilltop residents and businesses with resources, it is just as necessary to provide “equitable access to those resources and support to navigate and complete whatever is available … because if those things are not in place, the displacement will continue to happen,” Nelson said.

Finally, when working towards centrification, to ensure that development does not change the fabric of Hilltop, art and design must be used to uplift the community voice. This includes everything from larger scale projects, like designing buildings, to creating smaller scale public art installations. Nelson said, “It’s not just about art, it’s also about maintaining and capturing the history and culture of the community, which has been stripped away in so many ways.”

According to Nelson, who was also involved in the 2019 #DesignTheHill initiative, one way that art will be used to represent Hilltop’s history is through murals. “As you see the light rails come through, you’re going to see more depictions of leaders from the community from over the years,” he said.

In developing their parcels, THA is “working with local artists to, yes, put in art installations, but also to help in the design process of designing what the actual buildings look like in a way that is inviting to current residents, that maintains the feel of the neighborhood and the community and that reflects the historical culture of the community,” through projects including, “picking the color palettes for the building[s] and incorporating architectural pieces that are more reflective of the population that lives there,” Torrez said.

For instance, to help design the building on the parcel containing Mr. Mack Ltd. and Terry’s Barbershop, which the Horizon Housing Alliance, a non profit organization that provides housing to those in need, and THA are collaborating on the development of, the Horizon Housing Alliance hired local artist Tiffany Hammonds. “She worked with the architect to design the exterior facade. It’s done in traditional African colors and it’s something that your typical architect would never have come up with on their own,” Schur said.

THA is also working to collaborate with the other developers designing the buildings near the organization’s parcels in order to maintain the community’s artistic vision. Torrez said, “All the buildings will work together too. I think that’s kind of the idea behind having these artists, is they’re going to work together, so it’s not like one building and then a different one and they’re disjointed. It’s this idea of having kind of a shared vision.”

“A quilt,” Schur added.

This piece was originally published in Inkwell’s Social Justice Issue.